The path pivot attack

In April was published CVE-2017-2619, a race condition vulnerability affecting Samba. The vulnerability is described as follows:

Clients that have write access to the exported part of the file system via SMB1 unix extensions or NFS to create symlinks can race the server by renaming a realpath() checked path and then creating a symlink. If the client wins the race it can cause the server to access the new symlink target after the exported share path check has been done. This new symlink target can point to anywhere on the server file system.

Regarding the exploitability of this bug, the announcement adds:

This is a difficult race to win, but theoretically possible.

There is however another vector to exploit this vulnerability: when the shared folder is stored on a drive controlled by the attacker.

Getting started

Some network devices like home routers or NAS provide the ability to plug an USB external drive and share its contents on the network. This is for example the case in France for the DSL routers shipped with most ISPs.

Once a USB drive is plugged in, the system will detect its partitions, automatically mount them and create a network share on the LAN, usually using Samba.

One of the first easy thing to do is to create a symbolic link on the partition and verify that you can’t read files outside of the shared folder. Unless you are using an extremely old version of Samba, widelinks should be disabled by default and this should fail.

On the server side, this is what happens:

- A request is received for opening a file at

A - The path

Ais checked to ensure it is contained within the shared folder - If everything is fine, the file is opened

Samba uses the function realpath to canonize the path and verifies it is contained inside the shared folder. On Linux, realpath will in turn use the lstat and readlink system calls to resolve symlinks, while the final operation will invoke open.

This behavior can be confirmed by running strace on a vulnerable Samba. Trying to open the path a/b/c pointing to a file file shows:

stat("a/b/c", {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=0, ...}) = 0

getcwd("/mnt/shared", 4096) = 12

lstat("/mnt/shared/a", {st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=4096, ...}) = 0

lstat("/mnt/shared/a/b", {st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=4096, ...}) = 0

lstat("/mnt/shared/a/b/c", {st_mode=S_IFLNK|0777, st_size=4, ...}) = 0

readlink("/mnt/shared/a/b/c", "file", 4095) = 4

lstat("/mnt/shared/a/b/file", {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=0, ...}) = 0

stat("a/b/c", {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=0, ...}) = 0

getxattr("a/b/c", "system.posix_acl_access", 0x7fff672973c0, 132) = -1 ENODATA (No data available)

stat("a/b/c", {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=0, ...}) = 0

open("a/b/c", O_RDONLY) = 12

Since those operations are not done in an atomic way, there is no guarantee that the file we checked is the same file as we opened.

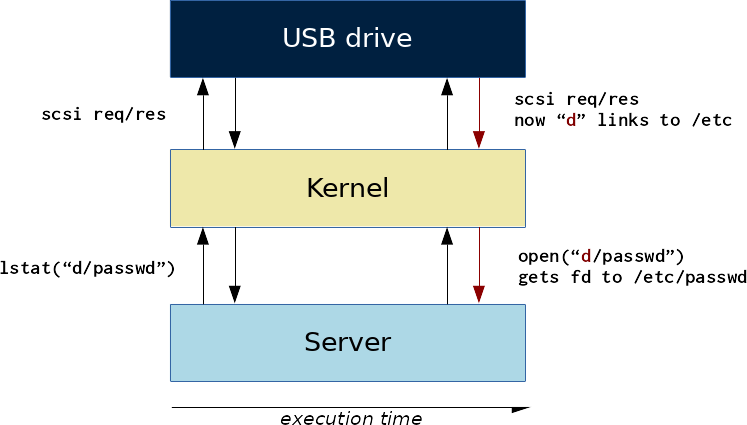

The principle behind the attack is to trick the OS by making the realpath and the open operations work on different files using a fake USB storage drive.

Exploitation

The most obvious way for exploiting this design flaw would be to trigger a remount of the partition between the call to realpath(path, ...) and the call to open(path, ...). This way not only would they operate on different files, but also on different filesystems. This is however unpractical for a number of reasons:

- the race condition is almost impossible to win

- most devices I have seen will kill the server when the device is detached

Since we control the storage device, a better idea will be to detect the call to realpath during the access to some disk sectors, and later return some different data during the open operation.

The filesystem cache

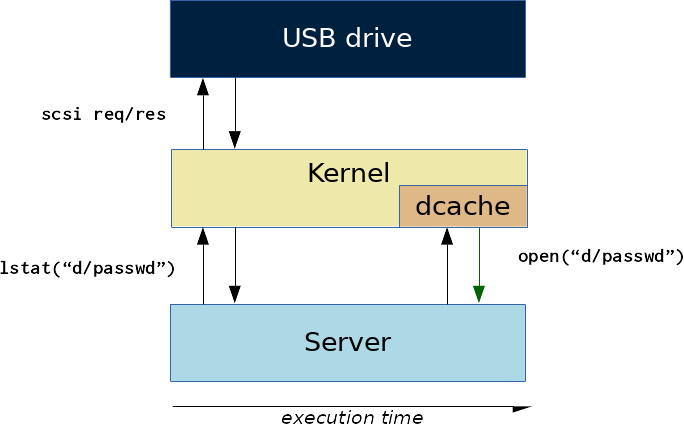

In practice, modern operating systems are pretty much optimized for reducing the number of I/O accesses. During a path resolution, the Linux kernel may have to fetch information for a path component by reading the disk, but it will not do it again if it does not need to. Instead, this information is kept in memory into the dentry cache (or dcache).

The dentries are the kernel structures associating a name to an inode. For a local filesystem, they remain in the dcache undefinitely until the kernel reclaims the memory for some other use.

Consequently, the path resolution during open will lookup each path component in the dcache first, and the device will simply not be queried.

However the cache is used for performance reasons, it is not meant for security. It is in fact possible to reliably remove entries from the cache between the two calls as we are going to see.

Invalidating the cache

The Linux dcache is a LRU cache, which means the first entries to get replaced are the ones that are the least recently used. The cache also does not have a fixed size. It will occupy as much memory as possible but the kernel reserves itself the right to shrink it and reclaim the memory whenever it is needed elsewhere.

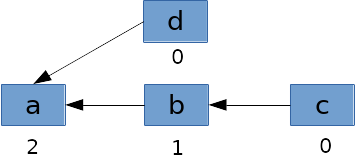

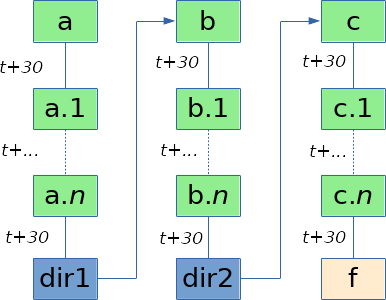

When memory is reclaimed, the kernel will enumerate the dentries in the cache and garbage collect those that are unused (for which the reference counter is equal to zero). Each dentry holds a reference to its parent dentry. The kernel also keeps a reference to the current path component being looked up. Let’s consider the resolution of the paths a/b/c and a/d. After the path resolution, the tree of dentries would look like this:

The kernel would first garbage collect c and d, which would then be followed by the collection of b, then of a. But if this were to happen during the lookup of component b, the kernel would not be able to free it, nor a, because their reference counters would not be zero.

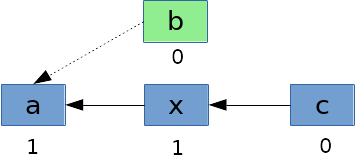

Now the situation is little different when symlinks are involved in the path. Let’s consider the case of a path a/b/c but where b is a symbolic link to a directory a/x.

During the resolution of b, the kernel will follow the symbolic link and continue the path walk at x. The symbolic link b will keep its reference counter to zero and it can be removed from the dcache even during the path resolution.

It means that by putting a symlink in a path, there is the possibility for its dentry to be freed by the kernel before the return of the lstat system call. The disk will then have to be read again during the following call to open with the same path.

At first it may seem improbable for a cached dentry to be removed during the short lapse of time of a few syscalls, but actually it is possible because we can make the whole operation go very slowly. By delaying the SCSI response packets, we can leave the system call in a blocking state. Linux will wait by default 30 seconds by SCSI request before considering the disk as being dead. By staying under this threshold and by following a lot of symlinks, we can easily make a simple realpath take an hour and still return correctly.

If we consider a path a/b/c pointing to a file f, we can chain a large number of symlinks together (but less than 40 to avoid an ELOOP error) and put them on different locations on the disk in order to drastically slow down the whole path resolution. We can also slow down the process even more by splitting the SCSI responses and returning smaller chunks of data or by creating intermediate directories with their inode on different physical locations.

While the realpath operation is stuck with slow I/Os in lstat and readlink, we can begin the process of evicting our cached symlink entries (the green boxes in the picture). Different strategies can be adopted for that aim. The easiest one is to perform a SMBLoris attack to create a high number of connections and allocate a lot of memory. Under high memory pressure, the dcache will shrink. It only takes a few seconds to fill the memory and for the dentries to get evicted, so the race is easily winable. Of course this would also work with any other DoS vulnerabilities leading to high memory consumption.

The time for the dentries to be evicted depends on the amount of RAM available on the device. It may require some calibration for the DoS to occupy enough memory to shrink the cache without triggering the OOM killer.

Building the fake USB drive

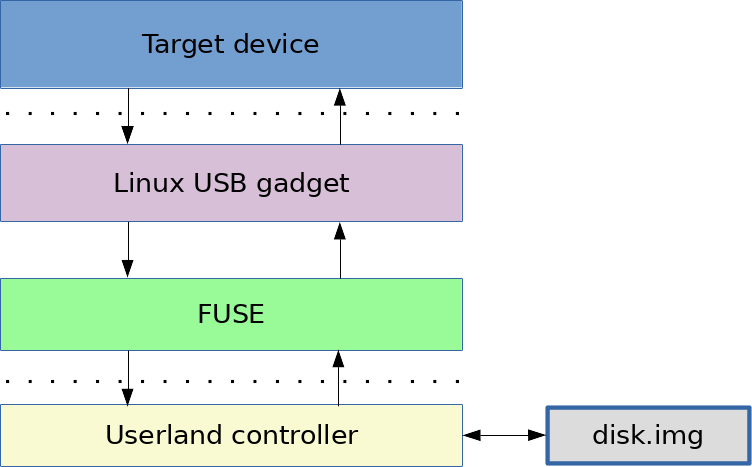

For creating our “slow drive”, we will need a device running Linux with an USB OTG port, for example a Raspberry Pi Zero.

Using the Linux module g_mass_storage and the OTG port, we can emulate a USB key. The module takes an argument file specifying the path to the disk image. We will specify that disk image to be in a FUSE mount point. This way we will control in userland every physical access to the disk.

SCSI READ commands are converted to vfs_read calls by the kernel module. This call is handled by FUSE and forwarded to a userland program. The userland application will read the disk image file and will possibly call sleep to delay the SCSI responses depending on what is being read.

Attack demo

The following demo will target a server running Samba 4.1.13. The partition is formatted with ext3 and contains a symlink tree xxx1/.../xxx39. Each xxx symlink redirects to a directory prefixed with magic_ that will be intercepted by our controller.

During a read operation, Samba 4 will do the following operations:

statthe target file and cache the result- Canonize the filename with

realpath - Check file permissions and ACL (

statandgetxattr) - Open the file with read access

fstatthe file descriptor and check the device/inode number has not changed since step1- Read the file

During step 1, we will pivot the stat call to point to /etc/passwd. During step 2, we will make the path point to a dummy passwd file. Then at step 3 we pivot again to /etc/passwd . This way we effectively bypass the checks at steps 2 and 5.

Note that the server has 1 GB of RAM, and the DoS had been calculated to create and destroy the right number of processes. In order for the attack to succeed, you also have to use a Samba client that will not timeout when the server takes too long to respond. I used a custom script relying on pysmb here, but this can also be done with a patched smbclient.

Final words

Samba versions starting from 4.4.12, 4.5.7 and 4.6.1 are not impacted anymore by this vulnerability. The source code used for the attack can be found on GitHub.

It is worth noting that this kind of attack can be extended to different scenarios. This type of attack could potentially also apply to:

- UPnP multimedia servers (DLNA)

- devices offering a file browser for an external drive (image viewers, multimedia players)

- firmware updates with their signature being verified while being stored on a USB key

The rule of thumb is to not assume that an external disk will return the same values across calls. Be extra careful when manipulating files stored on an external drive!

Comments